Note: Assignment 5 is a double assignment. Each milestone (MS1 and MS2) is worth 1/6 of the assignments grade for the course, equal to (individually) Assignments 1–4.

Due:

- Milestone 1 due

Wednesday, Apr 20thThursday, Apr 21st by 11pm - Milestone 2 due Friday, Apr 29th by 11pm (you may submit by 11pm on Monday, May 2nd

without penalty

, but submissions beyond this point will not be accepted!): you may use late hours on Milestone 2, but- they are counted from the nominal due date of Friday 4/29, so you need at least 72 late hours remaining to submit later than 11pm on Monday 5/2, and

- You must explicitly request to use your late hours this way (email daveho@cs.jhu.edu if you are interested)

Update 4/13: Adjust weights so that MS1 and MS2 are equal

Update 4/14: Added Demo recording, Automated testing support,

and updated the skeleton project (csf_assign05.zip) to fix an

issue with the reference server implementation (ref-server).

If you’ve already started working on the assignment,

you can update your reference server by running the following commands

in your project directory (make sure you’ve committed and pushed

all of your work first, just to be safe):

wget https://jhucsf.github.io/spring2022/assign/csf_assign05.zip

unzip csf_assign05.zip csf_assign05/reference/ref-server

mv csf_assign05/reference/ref-server reference

chmod a+x reference/ref-server

rm csf_assign05.zip

rm -r csf_assign05

Update 4/16: There was an error in the solution.zip target of the Makefile

in the original project skeleton. To fix it, change the zip command from

zip -9r $@ Makefile *.cpp *.c README.txt

to

zip -9r $@ Makefile *.cpp *.c *.h README.txt

Update 4/18: There was an error in the automated test scripts for the MS1 when run on the ugrad machines. You can fix this by re-downloading the scripts.

Update 4/22: We have provided a screencast which demonstrates various manual testing scenarios using the reference server, your clients, your server, and/or netcat. See the (end of the) Testing section.

Update 4/25: You may submit MS2 by Monday, May 2nd without penalty.

Update 4/25: We have added automated testing instruction for the server.

Update 4/27: server_skel.cpp is a partially-implemented

server.cpp that demonstrates an approach to accepting connections, starting client

threads, and using a Connection to communicate with the client.

See the Partial server.cpp implementation

section.

Overview

In this assignment, you will develop a chat client program that communicates synchronously with a server in real-time. You may think of this as an implementation inspired by classical chat systems such as IRC.

You can get started by downloading and unzipping csf_assign05.zip.

Note: We highly recommend that you use C++ for this assignment. The server is

easier to write with abstractions such as scoped locks and classes. It is also

very useful to use C++ classes to represent important objects in the client

and server implementations, such as Connection and Message.

The provided skeleton code includes partially implemented classes which

we encourage you to use as the basis for your client and server implementations.

Grading Criteria

Milestone 1:

- Implementation of sender client: 22.5%

- Implementation of receiver client 22.5%

- Design and coding style: 5%

Milestone 2:

- Implementation of server: 30%

- Report explaining thread synchronization in server: 15%

- Design and coding style: 5%

Goals of the assignment

The main goal of the assignment is to provide an opportunity to create a network application.

Although this will be a relatively simple program, it is representative of a larger class of network-enabled systems:

- It will have a protocol for communication between clients and server

- it will allow communication over a network (specifically by accepting TCP connections from clients)

- It will use concurrency and synchronization primitives to coordinate access to shared data on a remote server

Demo

Here is an example chat session with three different senders and one receiver, all connected to the same server:

(thanks asciinema for the wonderful terminal recording widget!)

The Protocol

The client and server communicate by exchanging a series of messages over a TCP connection. There are two kinds of clients: a receiver which is used to only read messages from the server, and a sender that is used to send messages to the server. To allow multiple groups of people to talk independently, the server partitions clients into “rooms”. All receivers in the same room will receive that same set of message, and all senders in the same room will broadcast to the same receivers.

A message is an ASCII-encoded transmission with the following format:

tag:payload

A message is subject to the following restrictions:

- A message must be a single line of text with no newline characters contained within it.

- A message ends at a newline terminator which can be either

"\n"or"\r\n". Your programs must be able to accept both of these as newline delimiters. - The

tagmust be one of the operations specified in the “tag table”. - The payload is an arbitrary sequence of characters. If a tag has a structured payload, the payload must be formatted exactly as specified.

- If a tag has a payload that is ignored (e.g., the “quit” and “leave” tags),

the tag/payload separator character

:must still be present (e.g.quit:notquit), even if the payload is empty - An encoded message must not be more than

MAX_LENGTHbytes.

The first message sent to the server by a client is considered a login message, and must have one of the following tags:

sloginrlogin

These commands allow the client to log in to the server with the specified

usernames. slogin is for a sender, and rlogin is for a receiver. A receiver

terminates its connection by simply closing its socket. The server will

automatically detect when this happens by looking a send failure on the next

message sent to the client.

If a client logs in with slogin, from that point forwards, it is a synchronous

protocol. The client sends a message, and the server sends a response,

indicating the status of the request.

The following message types are defined:

| Tag | Sent by | Payload content/format | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| err | server | message_text | client’s request was not carried out. |

| ok | server | message_text | client’s request ran to completion. |

| delivery | server | room:sender:message_text | a delivery of a received message to a receiver. |

| slogin | sender | username | log in as sender. |

| rlogin | receiver | username | log in as receiver. |

| join | sender/receiver | room_name | client wants to join specified room (which will be created as necessary). Client leaves the current room if applicable. |

| leave | sender | [ignored] | the sender sends this command to leave the chat room they are currently in |

| sendall | sender | message_text | send a message to all users in room |

| quit | sender | [ignored] | client is done, server will close the connection. |

You may have the following assumptions about the usernames and room names we test your programs on:

- They will be at least one character in length

- They will contain only letters (

a-zorA-Z) or digits (0-9)

The reference server implementation will reject operations in which the username and/or room name do not meet these criteria.

Assignment skeleton

We have included a reasonably comprehensive assignment skeleton in the starter code to help you factor your design into manageable parts. You are free to change any part of the design, up to and including writing your assignment from scratch, so long as your program follows all semantics of the reference executables.

If you elect to change the skeleton code or the Makefile, ensure that you build executables with the sames names as the ones our Makefile builds. Do be especially careful if you elect to change our synchronization plans to prevent accidentally introducing sync hazards.

Here is a description of the files included in the starter code:

client_util.{h,cpp}- contain utility functions that are shared between the send client and receive client.connection.{h,cpp}- class describing a connection between a client and server. Used by both the receiver, the sender, and the server.csapp.{h,c}- functions from the CS:APP3e book. You are free to modify functions here as needed, e.g. adding const qualifiers for const correctness, but be careful if you don’t completely understand the function you’re changing!guard.h- RAII style block-scoped lock. Creating the object acquires the lock, destroying the object (i.e. when it goes out of scope) releases the lock.message.h- class representing the protocol message format.receiver.cpp- contains the main function for the receiver.room.{cpp,h}- room class used by the server.sender.cpp- contains the main function used by the sender.server.{cpp,h}- server class that tracks and aggregates the entire chat server’s state. Highly recommended that you follow the sketch presented here.server_main.cpp- Contains the main function for the server. If you implementserver.cppcorrectly above, you should not need to make changes to this file.

Milestone 1: The clients

For the first part of this assignment, you will be responsible for implementing the receiver and the sender to communicate with a server binary included in the starter code. Note that the following messages are considered unused and do not need to be handled by any client:

senduser

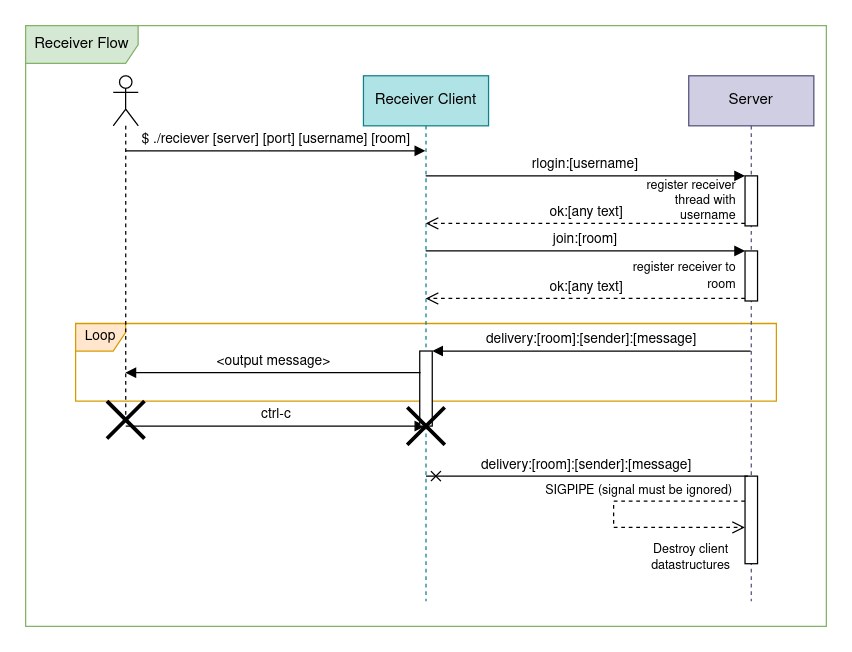

Receiver

The receiver will be run in the following manner from the terminal:

./receiver [server_address] [port] [username] [room]

The receiver must send the rlogin message as its first message to the server.

The following communication flow has been provided for your reference (note that

this only covers the “happy case”):

The receiver should print received messages in the following format to stdout:

[username of sender]: [message text]

The following messages must be handled:

rloginjoindeliveryokerr

If the server returns err for either the rlogin or join message, the

receiver must print the error payload to stderr/cerr and exit with a

non-zero exit code. The receiver does not need to exit cleanly, we expect it to

terminate it by sending it a SIGINT (a.k.a. <ctrl>+c).

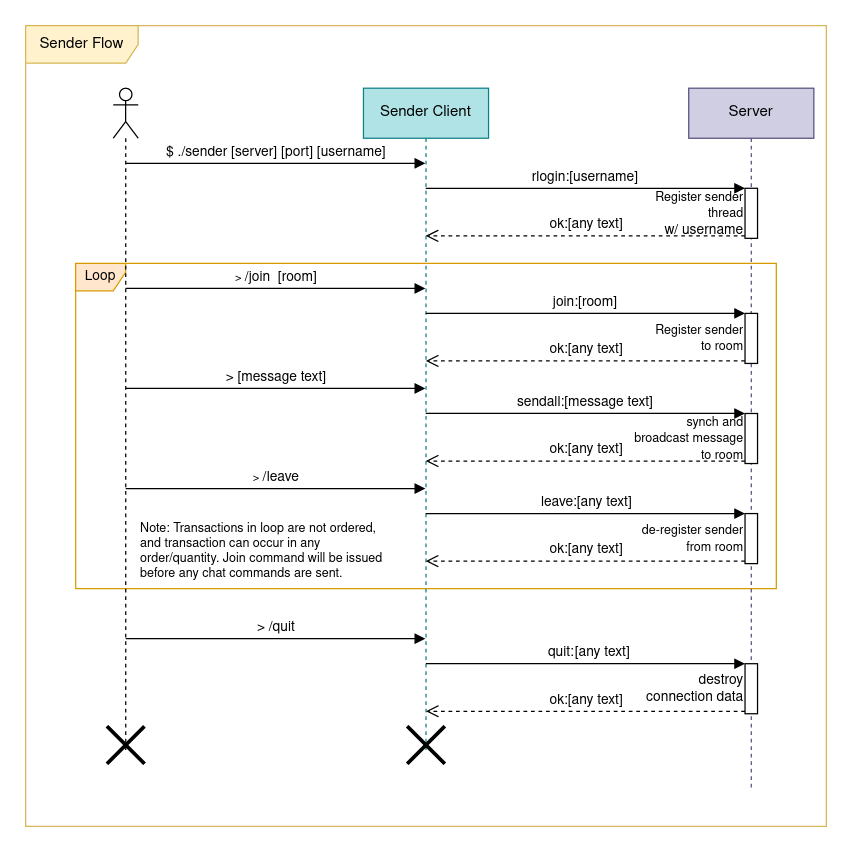

Sender

The sender will be run in the following manner from the terminal

./sender [server_address] [port] [username]

The sender must send the slogin message as its first message to the server.

The following communication flow has been provided for your reference (note that

this only covers the “happy case”):

The following messages must be handled:

sloginjoinsendallleaveokerr

After the sender logs into the server, it should read stdin for messages and

commands. Commands start with the / character and may be one of the following:

/join [room name]- joins the specified room on the server using ajoinmessage/leave- leaves the current room, stopping all message delivery using aleavemessage./quit- Instructs the server to disconnect the current send client using aquitmessage.- All other commands should be rejected with an error message printed to

stderr/cerr

You may assume that all command arguments are valid if the command matches a recognized command.

The client must listen for a response from the server after sending each message

(synchronous protocol). It is okay to stop reading user input during this time.

If the server returns err for the slogin request, the sender should print

the error payload to stderr/cerr and exit with a non-zero exit code. If the

server returns err for any other request, the sender should print the error

payload to stderr/cerr and continue processing user input.

If the quit commend is issued, the sender must wait for a reply from the

server before exiting with exit code 0.

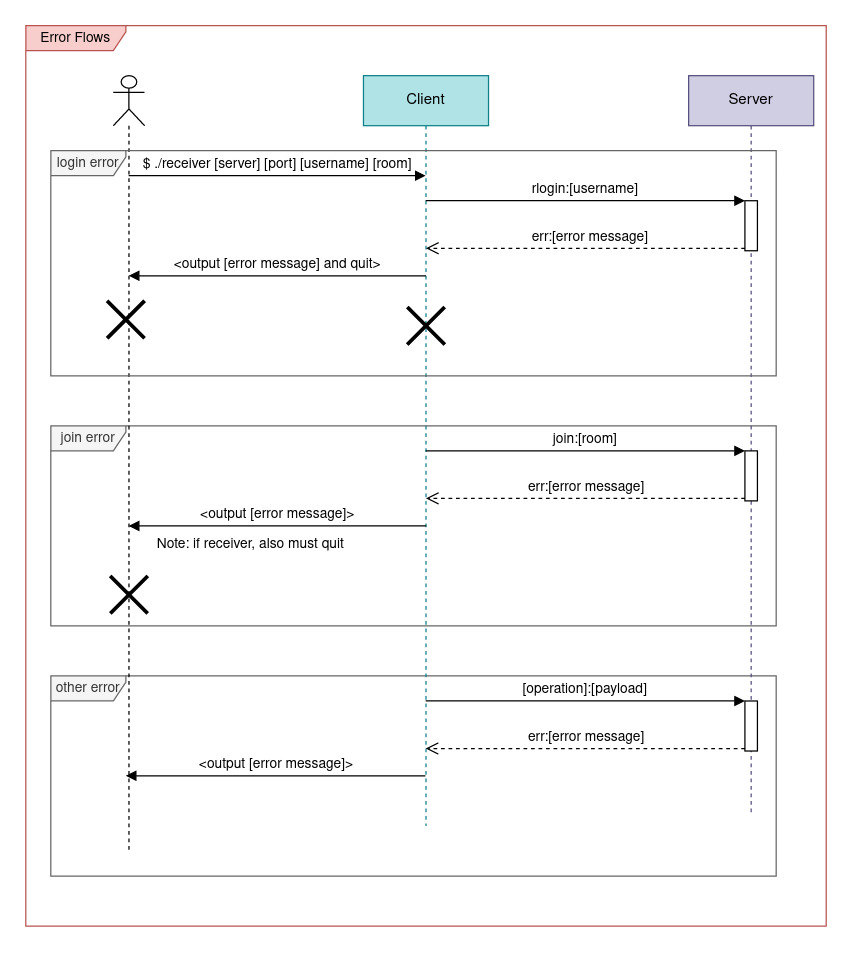

Error Handling

The following diagram summarizes how errors should be handled:

Each error message must be exactly one line of text printed to stderr/cerr. The

error text printed must be exactly the payload returned from the server in the

err message for server-side error. You may assume that this payload will

always be correctly formatted. For client-side errors, you may choose any error

string you want so long as it follows the specifications above and is suitably

descriptive.

You must handle failures to open the TCP communication socket by printing an informative error message and exiting with a non-zero exit code. You may assume that the server will stay online for the entire duration of the chat session.

If a client to run with the incorrect number of arguments, a descriptive usage

message should be printed to stderr indicating how the program should be invoked.

Implementation Tips

You are free to use any functions in the provided csapp.h header. In

particular, we recommend that you use the rio_* family of functions for writing

to the TCP socket file descriptors instead of using the raw syscalls. TCP

connections have significant latency that requires read to be buffered correctly

for expected behaviour. Remember that rio_readlineb does not strip the

newline characters.

To open the client connection to the server, we recommend using the

int open_clientfd(char* hostname, char* port) function. This function accepts

a hostname (server address) as a string and the desired port as a string, and

returns a file descriptor that is ready for use with the rio_* family of

function.

Testing

To aid your testing your program, we have provided a sample server implementation as a Linux binary in the starter code (see the Reference implementation section below.) We have intentionally compiled it without debugging information and stripped it of any symbols. If your clients are implemented correctly, you should be able to type in a message and see the message appear on all read clients in the same chat-room. You may run our server binary using the following command:

./reference/ref-server [port number]

We have only tested the binary on the Ugrad systems, and do not guarantee that it will work anywhere else. It definitely will not work on Mac computers, but may work on certain versions of WSL2.

Where [port number] is any integer greater than 1024. If the server fails to

open on the given port, try another one. You must specify the same port between

the clients and server.

You can also test one client at a time by using netcat as follows:

nc localhost [portnumber]

You can also spawn a netcat “server” using the following commands:

nc -l -p <port>

where port is a number greater than 1024. You would then type in the server responses yourself in the netcat terminal window after you get a client connected to the “server” following the sequence diagrams above.

You can then pretend to be a receiver by sending a rlogin request:

rlogin:alice

join:cafe

sendall:Message for everyone!

Or you can pretend to be a sender by sending a slogin request:

slogin:bob

join:cafe

<messages will appear here as they are sent to the room "cafe">

Do not valgrind netcat as that will not be testing your program, and may

generate false positives. Instead you should only valgrind the client executables

that you write.

We have recorded a screencast which demonstrates several testing scenarios using combinations of the reference server, your clients, your server, and netcat:

https://jh.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=3d9460a0-eca0-487b-8609-ae7f01050601

We also have a recording of a terminal session where we demo some of these manual testing workflows:

Automated testing

You can obtain the automated test scripts here:

You can download them on the in the terminal by using wget [link] while you

are in the same directory your project is in. Don’t forget to make them

executable after downloading them using chmod u+x [file].

test_receiver.sh is invoked as follows:

./test_receiver.sh [port] [sender_client] [room] [server_in_file] [output_stem]

and test_sender.sh is invoked as follows:

./test_sender.sh [port] [sender_client] [client_in_file] [server_in_file] [output_stem]

Note that test_sender.sh exits with the exit code the client exited with, so you

can verify that your client exited with the correct exit code by running echo

$? immediately after running the test script.

The arguments are:

port- port to run server on. Pick anything above 1024*_client- name of the client binary to run.room- room to connect the sender toserver_in_file- file containing list of messages server should send, one message per lineclient_in_file- file containing list of user inputs to the client, one per line.output_stem- base filename for the output, the files[output_stem]-received.out,[output_stem]-client.out,[output_stem]-client.errwill be created which correspond to the messages sent by the client to the server, the output the client printed tostdout, and the output the client printed tostderrrespectively.

While we highly encourage you to come up with your own test inputs, we have provided the following test inputs for reference:

You can run the example receiver test using:

./test_receiver.sh 12345 receiver partytime test_receiver_server.in receiver_test

and you should verify that receiver_test-client.err is empty, that

receiver_test-client.out contains exactly:

bob: hi alice

robert_de_bobert: I have the cookies.

bob: cookies?

and that receiver_test-received contains exactly:

rlogin:alice

join:partytime

You can run the example sender test using:

./test_sender.sh 12346 sender test_sender_client.in test_sender_server.in sender_test

and you should verify that sender_test-client.err is empty, and that

sender_test-received contains exactly:

slogin:alice

join:partytime

sendall:Hello World!

join:cafe

sendall:get me 1 coffee

quit:bye

With the exception of the payload to quit (it can be any text).

Milestone 2: The server

For this part of the assignment, you will be responsible for implementing the server. The server is responsible for accepting messages from senders and broadcasting them to all receivers in the same room.

The server will be run in the following manner from the terminal:

./server [port]

where [port] specifies the port that the server should listen on.

Tasks

Your overall tasks are to:

- Create a thread for each client connection. You will need a datastructure to

represent the data associated with each client. We recommend that you use the same

Connectionclass you used in part 1 to represent these connections. You may use the login message to determine what kind of client is trying to connect. - Process control messages from clients.

- Broadcast messages to all receivers in a room when a sender sends a message.

- Add synchronization for access to share data structures (

Rooms,Server) so no messages are lost, even if a receiver leaves or tries to join in the middle of a broadcast. You also must not lose messages that are sent at the same time from two different senders.

Using threads for client connections

In general, it makes sense for server applications to handle connections from multiple clients simultaneously, as servers are typically responsible for coordinating data exchanges. Threads are a useful mechanism for handling multiple client connections because they allow the code that communicates with each client to run concurrently.

In your main server loop (Server::handle_client_requests() if you are following

our scaffolding), you should create a thread for each accepted client

connection. Use pthread_create() to create the client threads. You will

probably want to create a struct to pass the Connection object and other

required data to the client thread, and use worker() as the entrypoint for

the thread. It may also be a good idea to create User object in each client

thread to track the pending messages, and register it to a Room when the

client sends a join request.

You can test that your server handles more than one connection correctly by spawning multiple receivers and senders on the same server, and checking that the messages sent from all senders get correctly delivered to all receivers.

Receiver and sender loops

If you are following our skeleton, we recommend that you separate the

communication loops for the senders and receivers into the chat_with_sender()

and chat_with_receiver() functions respectively. Please refer to the flow

diagrams in Part 1 to determine how you should implement these loops.

We have already handled the SIGPIPE signal for you in our provided server main

function, so you should be able to detect partial reads by matching the return

value of rio_* against the size of the message transmitted. If they do not

match, you may assume that a transmission error has occurred and handle

accordingly.

For all synchronous messages, you must ensure that the server always transmits

some kind of response (err for error, ok for success) to receive full

credit. Important: You must ensure that you skip sending a message to a

client with the same username as the sender of a message. For example, if Alice

sends a message, all receivers logged in as Alice must not receive that

message.

In the receiver client loop, you must terminate the loop and tear down the client

thread if any message transmission fails, or if a valid quit message is

received. For the sender client loop, you must terminate the loop and tear down

the client thread if any message fails to send, as there is no other way to

detect a client disconnect. Be sure that you clean up any datastructures and

entries specific to the client before terminating the thread to prevent memory

leaks.

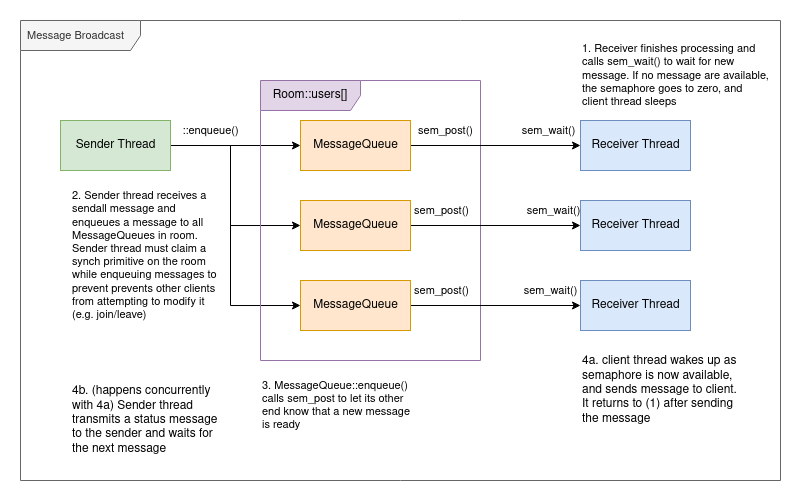

Broadcasting messages to receivers

To make synchronization easier, we recommend that you implement the pub/sub

pattern, using the MessageQueue class we outlined for you. In this pattern, a

sending thread iterates through all the Users in a room and pushes a message

into each MessageQueue. This event wakes up the receiver thread, allowing it

to dequeue the messages at its leisure. Here is a diagram of how this could

work:

Queues are a useful paradigm here because they allow us to receive messages at a different rate than we send them. If we had to wait for all messages to finish sending before releasing the lock on the room, we could end up spending all of our time servicing send requests, which would bring the server to a standstill.

To implement this “notification” behaviour, we recommend that you use a

combination of a semaphore and a lock. The lock ensures that the message queue

can only be modified by one thread at a time, and the semaphore is used to

“notify” the other end that a new message is available. Recall that a semaphore

blocks a thread when it goes below zero, and can be incremented (sem_post) and

decremented (sem_wait, sem_timedwait) from different threads. Thus, we can

essentially use the semaphore in each MessageQueue as a sort of “smart”

counter of the available messages in the queue. This implements the correct

behaviour: if there are no messages available, we want the receiver to sleep until

there are available messages, and each time a message is sent, it reduces the

available messages by one.

The sender client thread may return a response to the sender as soon as the message is done being added to all MessageQueues. It does not need to wait until the message has actually been delivered to all of the receivers in the room, but it should not return a status until the message is done being enqueued.

Note: While we recommend sem_timedwait() in the starter code, sem_wait() is

also acceptable for simplicity. (Using sem_timedwait() has the advantage

that the thread handling a connection with a receiver will not be blocked

indefinitely if there are no messages waiting to be delivered to that receiver.)

Synchronizing shared data

Synchronization is typically necessary when multiple threads can attempt to access the same data at the same time. Synchronization may also be necessary if certain semantics are desired of accessed to shared data (e.g. guaranteed ordering).

Strictly speaking, if the data type is atomic, read accesses need not be synchronized so long as they can probably never occur at the same time as a write. However, for this assignment, we are not using atomic types, so you will need to synchronize all concurrent access.

The section of code where synchronized access to data is implemented is called a “critical section”, and should be limited in length as concurrency is greatly restricted in these sections. Making critical sections too long can potentially cripple performance in real-world applications.

Add synchronization to the Server, MessageQueue, and Room objects to

ensure that updates to these objects will never be lost, not matter how the

objects are accessed. For example, if multiple clients try connect to the server

at the same time, both clients must be registered correctly, without losing

either one. Likewise, if two clients try join a room or send a chat at the

same time, both requests must be successfully carried out, with neither

operation “lost” or partially completed.

In a more practical sense, you may want to introduce a mutex to the Server,

Room and MessageQueue objects, and then add critical section(s) where needed

to ensure that the synchronization requirements are met. Very important: You

should not allow critical sections to be accessed across object boundaries to

prevent synchronization bugs. For example, if you implement a mutex in the

Room class, you should make it private and only synchronize to it from Room

methods.

Consider your synchronization hazards carefully! There are a few cases that may cause data races that are not immediately obvious (e.g. you must ensure that clients never broadcast and join/leave the room at the same time to prevent races).

Guard locks

To help prevent you from introducing deadlocks, we have provided a “block scoped

lock” implementing the “Resource Acquisition Is Initialization” (RAII) pattern

in guard.h. This means that constructing the Guard object tries to claim the

lock, and allowing it to go out of scope releases the lock. If you need the lock

to be held for a shorter scope than the entire enclosing block, you can

introduce additional scoped blocks:

void foo(pthread_mutex_t *lock) {

...

// introduce new block scope

{

// Aquire lock, blocks thread until lock becomes available

Guard(*lock);

// do something with the lock held

// invariant upheld: only one thread may enter this section at a time.

...

}

// lock is RELEASED here, and threads will be concurrent

...

}

We highly recommend that you use Guard objects instead of raw calls to

pthread_mutex_lock() and pthread_mutex_unlock(), as the block scoping

ensures that you will never forget to release the lock, preventing a vast class

of possible deadlocks. Remember that pthread_mutex_init must be called exactly

once on each mutex before it can be used.

Synchronization report

Since synchronization is an important part of this assignment, we’d like you to support a report on your synchronization in your README.txt. Please include where your critical sections are, how you determined them, and why you chose the synchronization primitives for each section. You should also explain how your critical sections ensure that the synchronization requires are met without introducing synchronization hazards (e.g. race conditions and deadlocks).

Error Handling

If the server fails to bind the listen TCP socket for any reason on the host,

you must print a descriptive error message to stderr and return a non-zero

return code. Once the server binds the port and starts listening for clients, it

does not need to handle actually shutting down.

We expect your server to be robust. This means no matter what any client

sends, in any order, your server should not crash. Note that to ensure this is

the case, you probably will want to use the rio_* functions, and the

Connection class you implemented for the clients. Some (non-exhaustive)

examples of bad things the client may do that should not crash your server

include:

- Sending messages longer than

Message::MAX_LEN - Sending invalid messages that cannot be parsed, including empty messages.

- Sending messages with invalid tags.

- Leaving and joining at any point in the communications sequence.

- Attempting to send a response to a client that has dropped off between the time a message was sent and before it could accept its response.

If a message cannot be parsed, could not be carried out, or is not a valid

message, you must send an err message to the client with a descriptive

payload. If a sender tries to send a message or leave a room while it is not in

a room, you must also return err with a suitable payload. This should not

stop the server, nor disconnect the client. Otherwise, you must send an ok

message with suitable payload. Failure to send a response to a client operating

in synchronous mode at any time one is expected is a severe bug that will

cause most tests to fail.

All client data should be cleaned up as soon as the server detects that the client connection has died. You may assume that any transmission error indicates that a client has died. It is okay if receivers are not cleaned up until the next broadcast is sent to a room for ease of implementation.

Since your server has no way of shutting down, you may ignore the “in-use at exit” portion of valgrind. You should still fix any leaks (section marked “definitely lost”), and invalid reads, writes, and conditional jumps

Partial server.cpp implementation

You can use the following partially-implemented server.cpp as a starting

point: server_skel.cpp. It demonstrates an

approach to accepting client connections, starting client threads, and

communicating with the client. Note that it does not implement the details

of the protocol that the server should use to communicate with receivers

and senders.

Assuming that your Connection class is fully implemented, if you build

the server implementation using this partial implementation, you should

be able to run and test your server, and use netcat as a client to connect

to it.

For example, start the server in one terminal using the command

./server 33333. (You can substitute a different port number.)

Then, run nc in a different terminal. Here is an example session

(user input shown in bold):

$ nc localhost 33333

slogin:alice

ok:welcome alice

join:partytime

ok:this is just a dummy response

sendall:Hello world!

ok:this is just a dummy response

quit:quit

ok:this is just a dummy response

^C

Note that the server does not actually process the quit message,

so you will need to terminate the connection using control-C.

Implementation tips

Start early! There are quite a few things you will need to think through in order to create a submission that receives full credit. We recommend that you start by implementing the logic that waits for new client connections and spawns client threads to handle them. If you are struggling with synchronization, we recommend that you reach a basic implementation without them, which might help you identify critical sections.

We recommend that you use detached threads. This means that you will not have

to join them back to the primary thread, and that you do not have to save the

pthread_tfrom pthread_create(). There are two safe ways to do this.

This first is to initialize a pthread_attr_t struct with the correct flags

using pthread_attr_setdetachedstate(), and pass this into the relevant

argument for pthread_create(). The second is to call

pthread_detach(pthread_self()) from the child thread. Under no circumstances

should you attempt to detach the thread from the creating thread as that risks a

data race.

Don’t forget to initialize your synchronization primitives before use. For

pthread_mutex_ts this is pthread_mutex_init(). For semaphores, this is

sem_init(). Use of synchronization primitives before they are initialized is

undefined behaviour and may not impose synchronization semantics as you expect

them to be applied. You should also destroy your synchronization primitives when

you release their associated resources. Failure to call the destruction

functions may result in leaked memory.

Do not attempt to share stack-allocated data between threads. This is undefined behaviour and generally causes the strangest bugs. Instead, ensure that any data that must be accessed between threads is part of a heap-allocation.

We also recommend using scope to your advantage. RAII resources such as the

provided Guard type prevent you from making mistakes like forgetting to release

resources, and defining variables to the narrowest scopes they will function in

dramatically reduces the potential for subtle bugs to creep their way into your

program. Aim to fail fast and early on coding mistakes.

If the server appears to become unresponsive for a long period of time it has probably deadlocked, and you will need to examine your synchronization. If a server doesn’t bind a socket on a given port, try another one, as the port you are trying to bind may be already taken.

Testing

We have provided the testing methods below to help you ensure that your program is working correctly. We highly recommend against using the autograder as your primary testing solution. The autograder is designed to be robust and thorough, and intentionally does not provides test feedback to you. Instead, we recommend that you use local testing techniques so you can use tools like debuggers and print statements to help debug.

Manual Testing

To test this program, you may follow the instructions in the MS1

Testing section, replacing the invocations of your client with

reference/ref-[client]. Netcat testing will probably also be a good idea so

you can figure out exactly what your server is sending.

For example, to test a server implementation against netcat, you could open

three terminal windows. In the first, you would run ./server [port], in the

second you would run nc localhost [port] and send a rlogin message, in the

third you would run nc localhost [port] and send a slogin message. Then you

would follow the flow diagrams to send messages from your netcat “clients”,

verifying the server responses that appear. If everything works in manual netcat

testing, you would move onto testing with our reference binaries using a similar

approach, before trying the automated test scripts posted below.

Here is a capture of an example testing session:

Automated Testing

Here are some automated tests you can try:

Don’t forget to make these scripts executable using chmod u+x [script name]!

test_sequential.sh runs two senders, one after the other, and is invoked

using:

./test_sequential.sh [port] [first_sender_input_file] [second_sender_input_file]

[output_stem]

test_interleaved.sh runs two senders, alternating between them for each line

of the input file. I can be invoked as follows:

./test_interleaved.sh [port] [unified input file] [output_stem]

test_concurrent.sh does its best to break your server’s synchronization by

spawning all sorts of clients that try send data as fast as possible while

simultaneously switching rooms and disconnecting. It can be invoked as follows:

./test_concurrent.sh [port] [iterations] [settling time]

[output_stem] will set the file that contains the receiver output after each

run. [output_stem].out contains the output of the receiver, and

[output_stem].err contains the receiver errors. For the sequential and

concurrent tests, we always expect the first user to be bob and the second

user to be alice, and errors for their respective senders will be found in

[user].err. Please keep this in mind as you write additional tests.

While we highly recommend you write your own test cases, we have provided the following tests inputs as examples:

You can run the reference sequential test using the following command:

./test_sequential.sh [port] seq_send_1.in seq_send_2.in seq_recv

and you should get nothing in seq_recv.err, bob.err, alice.err, and the

following output in seq_recv.out:

alice: Hello everyone

alice: I am trying to purchase the cookies

alice: Please give me your headcount and the number of cookies you want

bob: Hi Alice

bob: This is Bob.

bob: I want a chocolate peanut cookie with walnuts.

bob: Thanks!

and you should ensure that your server does not print anything to stdout.

You can run the reference interleaved test using the following command:

./test_interleaved.sh [port] test_inter.in inter_recv

and you should get nothing in inter_recv.err, bob.err, alice.err, and the

following output in inter_recv.out:

alice: This is a message from alice

bob: And this is a message from bob

alice: each alternating line of messages...

bob: will be send by a different client...

alice: this test ensures that clients are served in order

bob: and that one client may not monopolize the entire transmission

and you should ensure that the server does not print anything to stdout.

Some good parameters to start the concurrency test with are 10000 iterations and

30 seconds of settling time. If the test succeeds, you should see Tests passed

successfully!. Increasing the number of iterations will increase the likelihood

of detecting a race condition. If the test ends with Failed to verify* try

increasing the settling time, but if increasing the settling time to over one

minute does not allow the test to pass, you probably have a race. However, do

note that having this test pass does not guarantee that your code is sync-safe.

You should run the concurrency test last, after you get all other functionality working. The concurrency test will exercise all parts of your server while it tries to cause race conditions.

Note that the server can be run under valgrind by setting the VALGRIND_ENABLE

environment variable to 1. For example, if you want to run the sequential test

with valgrind, the command would be run using VALGRIND_ENABLE=1

./test_sequential.sh .... You may ignore the reports for “indirectly lost”,

“possibly lost”, and “in use at exit”, and ignore leaks caused by pthread_*

functions. You should definitely fix invalid reads, writes, or conditional jumps

that are reported by valgrind.

Reference

In the reference directory of the project skeleton, you will find executables

called ref-server, ref-sender, and ref-receiver. As the names suggest, these

are the reference implementations of the server, sender, and receiver. Your

server, sender, and receiver executables should be functionally

equivalent.

Here is a suggested test scenario. You will need three terminal sessions.

In terminal number 1, run the server (user input in bold):

$ ./ref-server 47374

You can use any port number 1024 or above instead of 47374.

In terminal number 2, run the receiver (user input in bold):

$ ./ref-receiver localhost 47374 alice cafe

Make sure you use the same port that you used in the server command.

In terminal number 3, run the sender (user input in bold):

$ ./ref-sender localhost 47374 bob

/join cafe

hey everybody!

/quit

In terminal number 2 (where the receiver is running, you should see the following output):

bob: hey everybody!

Note that while the ref-sender program will terminate when the /quit command

is executed, the ref-server and ref-receiver programs will need to be

terminated using Control-C.

Submitting

You can use the solution.zip target in the provided Makefile to create a zipfile

you can submit to Gradescope:

make solution.zip

Upload your solution.zip as Assignment 5 MS1 or Assignment 5 MS2,

depending on which milestone you are submitting.

Make sure your Milestone 2 submission includes your README.txt describing

your approach to thread synchronization in the server.